Ticks & Livestock

Livestock-tick infestation can lead to loss of condition and sometimes death. There are 3 main ticks of concern in NSW.

Managing ticks in livestock

Spring is a common time for tick issues, as the various tick life stages emerge from dormancy and seek a host to feed off from late winter. This means there is a peak in tick paralysis cases from very early spring (even late winter) through to mid-summer.

A single engorged adult female paralysis tick (Ixodes) has enough toxin to paralyse (and kill) a young calf, sheep or goat and less than ten bush ticks (Haemophysalis) can transmit enough Theileria to cause anaemia and sometimes death in calves.

What is tick paralysis?

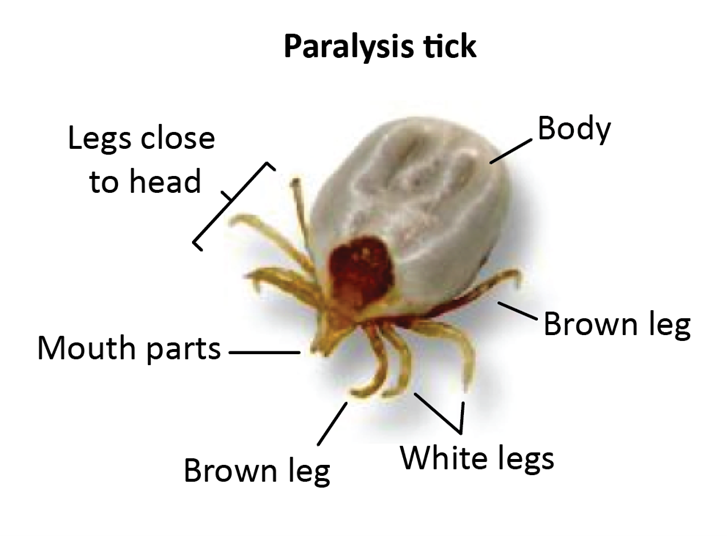

Paralysis ticks are a common cause of sickness and death in cattle, alpacas, sheep and goats. Paralysis ticks (Ixodes holocyclus) are native to Australia and their primary hosts are marsupials (bandicoots, wallabies, echidnas, and possums). The native animals are usually immune to the toxin injected by the paralysis tick’s saliva due to constant exposure to ticks. Unfortunately, they also attach to livestock and our domestic pets causing an ascending paralysis, recumbency, breathing difficulty and death if not treated.

Ticks are clever at hiding in hard-to-find locations (between hooves, nostrils, anus, vagina, inside ear canals or under fleece) and potentially may have dropped off by the time you are noticing clinical signs in your stock. If you have livestock showing symptoms of tick paralysis, then treatment with tick anti-toxin is available and reasonably successful if treatment is sought early and registered for use in livestock, through your private veterinarian.

The paralysis tick is called a three-host tick. This means throughout its life, the tick must attach to a host, feed, drop off and moult three times with each feed lasting approximately 1 week. The three stages in order are: Larvae (pin head size), Nymph (match head size) and Adult (pea-size). The paralysis tick spends more time on the ground than on the host animal and can survive off the animal for 6-8 months if it is not too hot or too cold (>32C and dry and <7C).

All stages of the tick can inject a neurotoxin into the host animal, but the adult tick injects a larger amount, which affects the nervous system of the animal. Initially you will notice that the animal loses coordination in the hindquarters and the paralysis slowly moves forward, affecting the front legs, breathing and swallowing. Young animals are more susceptible to ticks because of their low body weight and lack of previous exposure to ticks. Experiments have shown that it takes 2 adult ticks on a 2–3-week-old calf to cause paralysis.

As the animal becomes bigger, it takes more ticks to cause paralysis, and once the animal is exposed to ticks, it slowly gains a degree of immunity to the toxin.

Paralysis ticks are an issue all year around. We tend to see higher numbers of ticks when we have had high rainfall during the previous year, thick ground cover for protection of the free-living stage of the tick and where you will find a lot of wildlife.

Identifying and treating Tick Paralysis in livestock

Paralysis ticks can be easily missed on stock. Ticks are mostly found by feel. With careful searching you might find a characteristic tick crater left behind after the tick has dropped off.

- Signs of paralysis can occur from 3-5 days after attachment of an adult female tick. Thus, calves as young as 4 days old can be affected. Without treatment the animal dies within 1-5 days after signs of paralysis.

- Hind limb (weakness) is usually the first symptom and paralysis is ascending (progressively moving forward) until the animal is unable to rise.

- Tick paralysis starts with weakness in the hindquarters, which can lead to recumbency and death. Exposure of a weak or paralysed calf to hot weather, dehydration and predation is also a risk and paddocks must be inspected regularly to identify cases.

- As paralysis continues, an animal may not be able to maintain a sitting position and might be lying on their side unable to lift their head.

- Increased respiratory effort (might sound like grunting) and difficulty swallowing may become evident as paralysis increases.

- Death is usually from respiratory failure, aspiration of gut contents or pneumonia.

- Misadventure and an inability to move from environmental extremes may also contribute to the death toll, for example hot weather and dehydration. Affected calves are also prone to predation.

Treating livestock affected by Tick Paralysis

- Paralysis ticks must be removed. Amitrax is registered to kill both paralysis and bush ticks. It does not have a residual effect and while useful as a treatment, it is impractical to use in an extensive livestock situation as a preventative.

- Paralysis tick anti-serum (administered by your private veterinarian) can be given to neutralise any unbound toxin. If given early this can save the animal’s life. Advanced cases might have a guarded prognosis. We advise you speak to your private vet, as they can help you to work out the best course of action.

- Paralysed livestock cannot be left in the paddock untreated. After ticks have been removed and treatment administered, they need to be placed in the shade and nursed.

Prevention and control of Tick Paralysis

Prevention of tick paralysis can be difficult due to the tick’s short period of attachment to the animal and the large number in the environment. Most chemical products currently registered for control of paralysis ticks are labour-intensive to apply and offer short periods of protection.

Please be aware that there is an Australia wide shortage of paralysis tick anti-serum. This is a result of a sudden increase in demand due to tick resurgence. There is one main manufacturer of anti-serum and they are at full production capacity.

Please ensure all susceptible animals are being managed with paralysis tick preventatives (domestic dogs and cats have a range of suitable and very effective preventatives provided they are given religiously by the due date).

Paralysis tick prevention in ruminants has just become a little more difficult with the current unavailability of the synthetic pyrethoid insecticidal ear tags registered for paralysis ticks. These tags were very useful and were registered for use against paralysis ticks for 42 days. All other registered paralysis tick treatments are short acting sprays, pourons and washes.

There are several products registered for use on bush ticks in all animals and these may have some effect in preventing paralysis ticks. ALWAYS read and follow the label for chemical treatment options and be sure to obey withholding periods (WHP) and export slaughter intervals (ESI). It is also worth remembering that applications of unregistered chemical products is illegal in food producing animals (as well as generally being minimally effective).

Control is best achieved by preventing or reducing infestation. This can be achieved by altering breeding patterns so that vulnerable young stock are not being born during the time of highest risk (late winter/early spring).

For cattle, the infusion of Bos indicus breeds can increase innate resistance to ticks including paralysis ticks.

Creation of low-risk pastures also assists in reducing tick infestation. Paralysis ticks favour bushy or shrubby areas with large volumes of organic matter to provide shelter. Manage these risks by hard grazing or slashing of such paddocks and don’t use heavily vegetated paddocks for birthing, risks of infestation can be reduced.

What is Bush Tick?

The Bush tick (Haemaphysalis longicornis) is also a three-host tick, which means they spend most of their life in the paddock and only 5-7 days at a time on the beast. This means it’s not always easy to find ticks on livestock, and you may mistakenly think your property has no ticks.

Cattle are the preferred host of bush tick, although large infestations have been found on deer. Bush tick often infests other livestock (including sheep and pigs), as well as other warm-blooded animals such as dogs, horses and even humans. It also occurs on numerous wildlife species, and the immature stages have been found on birds.

Bush tick can be responsible for Theileria infection, which are parasites that infect and destroy red blood cells. Read more about Theileria.

What is Cattle Tick?

The most economically important tick affecting livestock in Australia is the cattle tick (Rhipicephalus australis – previously known as Boophilus microplus).

Cattle ticks can also survive on other livestock, such as sheep, goats and horses. It is a single-host tick and once the hatched tick larvae are picked up by the host, they spend all three parasitic life stages (larvae, nymphs and adults) on the same animal for about 21 days, when engorged female ticks drop off.

Infestation with cattle tick usually occurs within the endemic regions of Queensland, the Northern Territory and Western Australia.

Please remember that any tick infestation associated with stock deaths should be investigated to ensure that the Cattle Tick-carrying cattle tick fever hasn’t somehow made it way to your property. Cattle ticks can be identified, among other things, by their pale leg colour.

The Tickboss website is useful in identifying different ticks.

For further information: NSW DPI Primefact 1372 “Paralysis Ticks and Cattle” https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/animals-and-livestock/beef-cattle/health-and-disease/parasitic-and-protozoal-diseases/ticks/paralysis-ticks

Adapted from articles by district veterinarians Jocelyn Todd, Kylie Greentree and Lyndell Stone.