Flystrike

Flystrike is a major disease and welfare issue for Australian livestock, especially in sheep where fleece rot has occurred following heavy rainfall or flood events. Other livestock can be struck by blow flies where they have open sores. Flystrike impacts farm profitability through loss of productivity from struck animals, as well as through the time and cost of treating and preventing flystrike.

What is Flystrike?

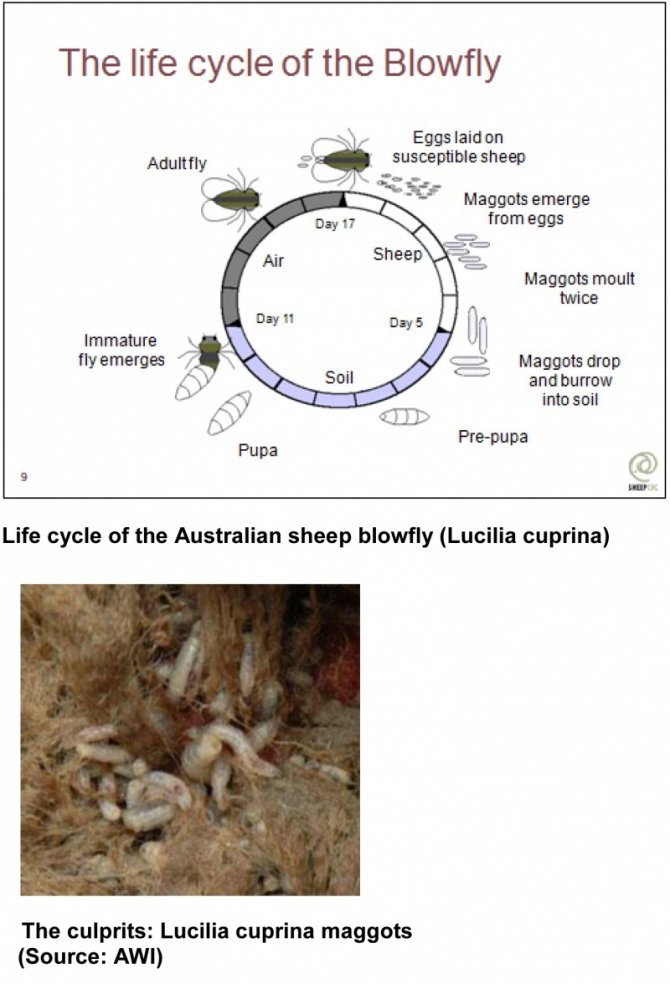

Flystrike is a painful condition that can be fatal if left untreated. Flystrike is caused when a blowfly lays eggs on the skin of the animal and the emerging larvae create an open wound as they feed on the underlying skin tissue.

The Australian sheep blowfly, Lucilia cuprina, causes over 90 percent of all flystrike in Australian flocks.

Maggots dropped into the soil during autumn have been in the pre-pupa stage in the soil over winter. The pupate and emerge as immature flies in the first few weeks of spring as the soil temperature rises above 15 degrees Celsius. These flies will have likely matured to adult flies and will have potentially started laying eggs on susceptible sheep, continuing the lifecycle and increasing fly numbers.

The sheep blowfly can mature up to 300 eggs in each cycle and lay a new batch of eggs every 4-8 days. These eggs hatch in as soon as 8 hours and the maggots immediately begin feeding on the sheep which is why it is vital to check sheep daily.

When to watch out for Flystrike?

Warm, moist conditions favour the breeding of blow flies.

Susceptibility of sheep to flystrike is determined primarily by fleece moisture. Moist wool can develop fleece rot and/or lumpy wool, which attracts blowflies. Urine- or faeces-stained wool, skin wounds, tissue damage such as footrot, weeping eyes and sweat around the base of the horns of rams can also make sheep susceptible. A wetter-than-average spring area increases the risk of moisture in the fleece and subsequent flystrike.

Paddocks with green feed increase the water component of faeces and those animals with excess wrinkle and wool will be more likely to suffer from breech strike. Monitor sheep closely, especially during high-risk fly periods, and treat struck sheep quickly. Controlling the risk of flystrike leads to better health and welfare outcomes for your sheep as well as more money in your pocket.

Clinical signs of Flystrike in sheep

Strike can be covert, can be detected early or can be advanced. These are the signs:

COVERT FLYSTRIKES

- Not easily detected, unless handling animal

- Small area of flystrike

- Can last weeks before advancing

- Can resolve without need for treatment.

Unfortunately, covert or hidden strikes are an important ongoing source of maggots which build up the fly numbers through a season.

EARLY DETECTABLE STRIKES

- Only detectable on close inspection

- Strike wounds will be small

- Sheep will show signs of irritation and discomfort such as:

- Biting

- Scratching

- Leg stamping and

- Ducking/hanging of the head

- Animals will still be a part of the mob

- Wool may appear lighter in colour from chewing or rubbing and will progressively get darker

- Depression of wool and body growth.

If you think an outbreak or fly wave might happen (a rapid increase in fly numbers bought on by an abundance of food and warm, wet weather), increase monitoring and take action. This includes crutching or chemical preventions as soon as possible. If shearers cannot be arranged, consider alternative options, such as additional jetting which may provide interim protection until shearing or crutching can be arranged. But be aware of any withholding periods, especially if planning to shear/crutch soon.

Identifying why the strike occurred will help you work out whether it is just one animal, in which case dramatic intervention may not be warranted, or if it is an indicator that an outbreak is imminent.

ADVANCED STRIKES

- Look for signs of systemic illness, which will typically progress over a few days. Signs include:

- Depressed

- Stop eating and drinking

- Weight loss

- Laying down

- Reluctant to rise

- Can’t keep up with the mob, be left behind and often found on their own

- Strike wounds will generally be large, wet and dark

- Maggots will be large and will be seen to be migrating out to consume healthy tissue

- There will be secondary strike from other flies, such as Chrysomya and Calliphora spp., they will be smaller but more serious as the maggots ‘underrun’ the skin and cause extensive damage and illness

- Skin will be swollen and inflamed

- Remaining fleece will become tender.

Without treatment, sheep with advanced strike will generally die quickly, anywhere from hours to three or so days. Early detection can help reduce flystrike, but if advance strike has been seen, you will need to monitor your flock more often as more strike is likely to occur in the following days. Once strike has been detected, the animal will need to be treated.

What should I do if I find a struck sheep?

Any sheep showing pulled or discoloured wool should be examined. Once identified, the struck area should be clipped with wide margins, allowing the skin to dry out and exposing maggot trails. The wool and maggots should then be placed in a black plastic bag and left in the sun to ensure the maggots are killed. The struck area should be dressed thoroughly with an appropriate registered chemical, preventing the area from being restruck as the wound heals.

Treating Flystrike in Sheep

- Shear struck wool with a 5cm barrier of clean wool around the strike zone. Make sure it is close to the skin and remove all maggots

- Collect all maggots and infected wool. Place into a plastic bag, preferably black and leave the bag in the sun for a couple of days to kill all the maggots.

- This helps to break the lifecycle of the fly as not all chemical dressings kill larger maggots, and many may escape treatment.

- Unless maggot infested wool is collected and bagged, most maggots will survive and pupate and come back as adult flies.

- Apply a registered flystrike dressing to the shorn area, preferably using a low-pressure applicator, to prevent re-strike. You will need to use a product that will prevent strike, while the animal is healing as some products do not last long enough to prevent restrike.

- Remove struck sheep from the mob and run separately to reduce the attractiveness of the mob to blowflies

- Ultimately, cull struck animals from your breeding program.

Although flies might seem a bit daunting, especially after last summer, the good news is, there are several great resources out there to help get you through.

How to prevent Flystrike

There is a range of insecticides available that you can use to prevent and treat flystrike. It’s important to rotate the use of chemicals to reduce resistance in the sheep blowfly. To date, there has been some medium to high resistance in the sheep blowfly reported in products containing dicyclanil, cyromazine and diazinon. To reduce the risk of resistance developing, you should not reapply the same chemical class for flystrike dressings, flystrike prevention or lice treatments within a single wool cycle.

In areas where flies are dormant for an 8-week period or more during winter, this is the best time to apply a preventative treatment to the entire flock.

Flystrike prevention is not just about applying chemical. While chemical application is a valuable tool in managing flystrike in your flock, it is important to use it strategically along with breeding and other management tools such as shearing, crutching and/or breech modification to further reduce the risk.

Flystrike can be highly repeatable, meaning that a sheep that becomes struck will likely be struck again in the future. If you have ongoing issues with flystrike, you should consider culling for strike, high-wrinkle and/or fleece rot scores as part of a wider genetic selection strategy for long-term prevention of flystrike in your flock.

Shearing or crutching is also a valuable tool in your armoury, as it can provide up to six weeks protection against strike. As daggy sheep attract flies, it’s also important to incorporate good worm control into management strategies to minimise dags and reduce the risk of flystrike.

When implementing shearing/crutching or chemical prevention strategies, it’s important to note that you should ideally undertake these strategies before soil temperatures increase and the first fly wave occurs. This will help keep fly numbers down for the rest of the season.

Management strategies can also play an important part of strike prevention. Control dags by treating underlying causes such as worms or bacterial diarrhoea. Think about the timing of shearing and crutching.

Chemical Resistance to Flystrike Treatments

Some local woolgrowers have been reporting resistance to commonly used chemicals. NSW Department of Primary Industries and Environment is conducting free resistance testing for producers. Kits can be collected at you nearest Local Land Services Office and whilst the process does take a couple of months (due to having to breed up enough maggots to conduct testing) it is very worthwhile and has been a real eye opener for some producers.

Flystrike is on its way - are you prepared?

Learn about how to plan and manage prevention of flystrike in your flock by listening to a leading flystrike expert in NSW, Narelle Sales.

Narelle will not only update your knowledge on chemical and management strategies for flystrike but will work through a case study to give you a real-time example of how to plan and manage the upcoming season.

Adapted from content by district vets Katelyn Braine, Linda Searle, and Sue Street.