Crop management options for a wet harvest

01 Nov 2021

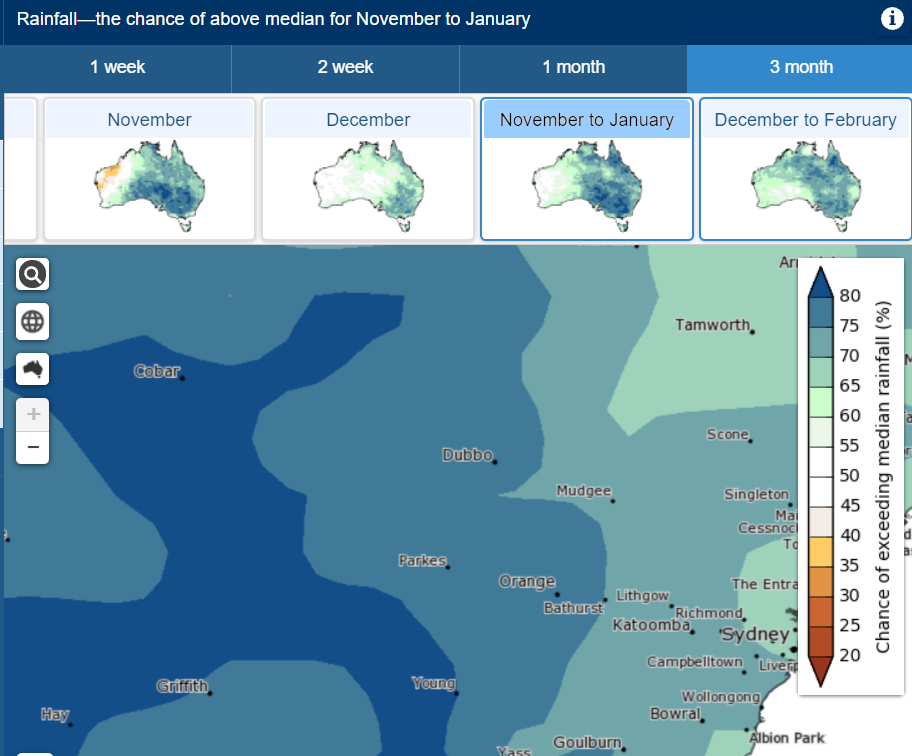

Right across the Central West, crops are ripening and harvesters are kicking into gear. However Mother Nature continues to present producers with headaches with a wetter than average harvest period predicted by the Bureau of Meteorology. There is an increased likelihood of above average rainfall across much of Australia during spring and early summer (http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/outlooks/#/overview/summary).

Figure 1: Climate outlook for November to January from the BOM website. The chance of exceeding median rainfall is at least 75-80% for most of the Central West and NSW - http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/outlooks/#/rainfall/median/seasonal/0

Figure 1: Climate outlook for November to January from the BOM website. The chance of exceeding median rainfall is at least 75-80% for most of the Central West and NSW - http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/outlooks/#/rainfall/median/seasonal/0

When pre-harvest rainfall is significant, moisture causes the seed to swell, often splitting the skin covering the growing point. This seed is referred to as being sprung. If wet conditions continue, the seed may complete its germination process and send out a shoot as well.

It is important to keep your options flexible going into a period like this. While a wet harvest may seem to be something that is beyond producer’s ability to control, there are a number of management considerations that can potentially make a wet harvest less stressful.

Crop type

Cereals

Crop species and type has a major impact during wet harvests. Crop species vary in their ability to withstand wet conditions and the effect that rainfall has on grain quality. Typically, cereals take longer to dry out than pulses or canola due to the architecture and thickness of the crop. Barley is also more susceptible to becoming shot and sprung when compared to wheat reducing yield potential and quality. Delayed harvest also influences oats as lodging becomes a problem and some varieties are more susceptible to being shaken out of the head when ripe and subjected to wind storms.

Pulses

While pulses may dry out faster in the field, they are very susceptible to downgrades caused by continued moisture. The moist conditions not only create ideal conditions for fungal growth and discolouration downgrades, but also damage the seed coating. This results in grain that is easily cracked and split resulting in reduced prices. In addition, chickpea yield losses of up to 30% have been recorded in the field due to delayed harvest due to pod drop and grain shelling out of pods well.

Canola

In general canola is better able to withstand wet conditions than most crops. This due mainly to plant architecture and the protection the seed pod provides to the seed.

Windrowing or swathing also adds another dynamic to consider. Windrowed crops take longer to dry out in very wet conditions, with the potential for windrows to go mouldy with downgraded grain. They are generally more protected from windstorms however newer varieties have been selected for tolerance to pod shattering and by direct heading canola (i.e. not windrowing), crops will dry out faster and be less affected by moisture.

Moisture Content (MC) management

As can be seen from Table 1, different crops have different maximum allowable MC which can be delivered to grain buyers. And as discussed in the previous section, these crops are drying out at different rates with pulses and canola faster than cereals. In addition, higher MC has been shown to reduce harvest loses in pulses through reduced shattering and damaged grain (GroundCover, 1999). Pulses should therefore be the first grain harvested after rainfall.

Table 1: Standard allowable MC % for grain delivered to GrainCorp this harvest. Values are an indication only and may vary depending on your grain buyer and local receival site.

Crop | Moisture Maximum (%) |

Wheat | 12.5 |

Barley | 12.5 |

Oats | 12.5 |

Canola (including GM) | 8.0 |

Chickpeas | 12.5-14.0* |

Faba Beans | 14.0 |

Lupins | 14.0 |

* Variation dependent on bunker storage (12.5%) or permanent storage (14.0%)

Aerated storage can also provide grain growers with harvest options. It is common practise in Europe and North America to harvest grain at 15% MC or higher and use aerated silos to dry down the grain. Aerated storage also gives producers more confidence to blend wet and dry grain by lowering the potential for wet pockets of grain forming and increases to fungal growth and insect populations. It is advised to turn the grain at least once during the drying cycle to avoid ‘hot spots’ from forming (Grain Growers - Factsheet).

Heated drying is suited to cereal grains with up to 25% MC, however under Australian conditions it is advised to harvest wheat at no higher than 20% MC. Portable or containerised grain dryers are used by some growers routinely, particularly in Queensland for sorghum and corn. Capacity of 10-30t/hour is common, reducing MC by 2% an hour. ‘Low and slow’ drying of grain is advised to avoid heating the grain too high and ruining grain quality. While the capital outlay and overhead costs for these can be quiet high, in wet harvest years they can earn very good returns by allowing growers to harvest high quality grain before moisture damage causes downgrades.

Strategies for aeration and heated drying of wheat may include harvesting at 18-20% MC, drying down to 15.5%. The grower could then transfer to an aerated silo and manage the moisture down to deliverable MC of 12.5%. While there are extra costs and handling required, this year a spread of around $100/tonne from APH1 and feed wheat may make it worthwhile.

Figure 2: Photo credit (https://www.headerfrontrepairs.com.au/services/harvester-front-repairs)

Harvest planning

By combining all of these strategies producers can implement a plan for a wet harvest. Talk to your grain buyer and identify your highest value crops and make these a priority for harvest. In a normal year, the barley price is around $20-30 under wheat while this year, that spread is much wider at around $60-70/t. Wheat therefore has a much higher downside risk to downgraded quality compared to barley, with feed grain prices much less this year than APW1.

The rate of harvest is also important to calculate. For example, if your header is harvesting 30 tonne of wheat worth $300/t per hour (gross value of $9,000/hour) compared to some wet canola worth $900/t going slowly at 15 tonne per hour (gross value of $13,500/hour) due to many stoppages, it may still be worthwhile getting the canola harvested before the wheat.

As you would all know, the preparation that goes into harvest is often what makes the difference in difficult years. A checklist to consider may include:

- Machinery that is cleaned and well serviced

- Clean silos that are free of pests and ready to be filled

- Other storage options like bags and pits

- Contractors in reserve especially considering Covid-19 state boarder closures

- Sufficient labour for the many harvest jobs required (listen to a recent episode of Seeds for Success with Jack Creswell to hear some tips on finding solutions to your labour shortages)

If you would like further information and harvest advice more specific to your situation please call your local Ag Advisory officer.

References

- Most of the information contained in this article was obtained from the GRDC GrowNotes for the Northern Cropping Region. Notes specific to crop species can be found here: https://grdc.com.au/resources-and-publications/grownotes/crop-agronomy

- Climate outlook for November to January from the BOM website as of 18/10/2021: http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/outlooks/#/rainfall/median/monthly/0

- Grain Growers, ‘Factsheet: Drying and Storing Weather Damaged Grain’ (April 12, 2013). Retreived from: https://www.graingrowers.com.au/drying-and-storing-weather-damaged-grain/

- GRDC GroundCover (1 June, 1999), ‘Harvest with higher moisture? The Reward and Risks’. Issue 27, retrieved from: https://grdc.com.au/resources-and-publications/groundcover/ground-cover-issue-27/harvest-with-higher-moisture-the-reward-and-risks