When can I sow my wheat variety?

By Tim Bartimote - Cropping Officer, April 2020

This is a common question asked of many advisors this time of year. Usually it is because a significant rain event has occurred or is forecasted to happen soon and the variety on hand is not recommended to be sown at that time of year. In this article I will discuss why we have recommended sowing windows for wheat, the reasons why you would stick to them and in what circumstance you may make the most of a rain despite being outside the recommended window of a wheat variety.

Deciding to sow a variety outside of its recommended planting window will significantly increase the risk of drastic yield reductions due to frost damage, if sown too early or heat stress, if sown too late. This is because recommended sowing windows are based around the idea that the variety will flower and fill grain during the period where frost and heat stress risk is at its lowest. This ideal flowering window changes from region to region, hence why some areas can sow one variety earlier than others. For more information on recommended sowing dates check out the Winter Crop Variety Sowing Guide in Further Resources.

Another consideration is soil temperature, a point made by Callen Thompson - Central West LLS Mixed Farming Officer, in a previous article (see further resources). For example, in cereals, sowing too early can expose seeds to high temperatures and significantly reduce establishment. It is recommended that oats be sown in soil temperatures between 25°C to 15°C while 25°C to 12°C is suggested for barley and wheat. Measure soil temperature at 9am, at sowing depth, over 3 days to see if it is adequate.

Apart from climate the other big driver in recommended sowing dates is the physiology of a variety. These are the drivers that cause a variety to move from vegetative to reproductive maturity. Varieties have been bred to react to seasons differently to achieve certain climates and production outcomes. These drivers are vernalisation, photoperiod and day degrees. The other non-physiological driver which can be included is grazing management in dual purpose varieties. Varieties are not strictly controlled by one driver but a varying combination where a certain driver may have more control over maturity than the others.

Vernalisation

Vernalisation refers to a plant's requirement to be exposed to a cumulative number of cold temperatures before flowering. Generally this occurs when exposed to temperatures below 12°C. Varieties with this vernalisation requirement, such as Wedgetail, can be sown earlier than others as they won’t race ahead if conditions suddenly turn warm as they would still need to meet their cold requirement.

Photoperiod

Photoperiod refers to a plant's response to a change in day length. A short day (less than 10 hours of light) will deter flowering in varieties with a strong photoperiod response. While a long day (over 14 hours) will accelerate a variety to flower. This is why some varieties, with a strong photoperiod response, are known to finish quicker.

Day Degrees

A day degree is the maximum temperature minus the minimum temperature of one day. Day degrees refers to the accumulated number of degrees that a plant has been exposed to over a certain number of days. In varieties where there is a limited vernalisation or photoperiod response, temperature is the main driver. For example, Gregory is known to flower after roughly 1500 day degrees. Hence maturity can fluctuate from season to season depending on whether the conditions in the season are warmer or cooler than usual.

Grazing Management

Finally, we can manage maturity to an extent with grazing management. However, this is not as reliable as the above mentioned physiological drivers. As maturity can only be delayed by 1, maybe 2 weeks at the very most. This is also assuming crops are evenly grazed across a whole paddock.

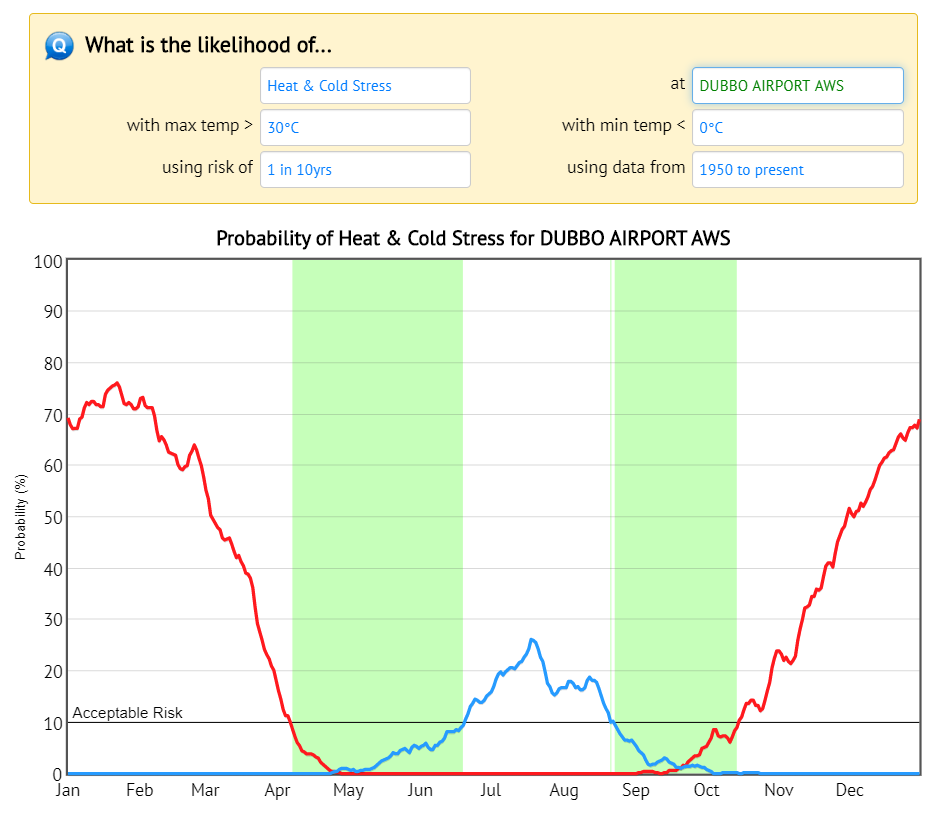

The NSW DPI has proved, over a number of studies, that maximising yield potential involves flowering during a specific window where frost and heat stress is at its lowest. This window changes from region to region and even between valleys. If you would like to determine the ideal window for your area, resources like Australian CliMate are useful in mapping climate trends from over the last 50 years and determining where risk is lowest. For parameters I suggest using a risk of 10% then include heat stress as >30°C and cold stress <0°C. Then determine from what year you would like to access data from e.g. since 1950 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Example of CliMATE modelling, depicting the likelihood of days without a max temperature of >30°C (heat stress) or a min temperature <0°C (cold stress) for the Dubbo Airport weather station, with a 10% margin for error. Flowering and grain fill for wheat would be ideal in late August and September for varieties in this region. This model is based on the last 70 years of temperature data.

After the last few years of drought, paddocks may have been bare for quite some time and producers may be concerned when another rain event may come. If you are just attempting to re-establish ground cover or purely providing feed for hungry stock then sowing too early, outside the recommended window, is an option as long as you understand that the risk for frost, in this example, will significantly increase and yield reductions are likely.

Understanding your local climate, your chosen variety and what drives it to maturity will allow you to make an informed decision on optimum sowing times. It all comes back to determining what your goals are. If the aim is to re-establish ground cover or provide winter feed for stock, despite potential yield reductions then that is a good outcome. Bear in mind, sowing quick varieties very early for feed will mean that the crop will run to head quickly and not achieve suitable biomass for grazing. It is still important to use varieties which are relatively suitable for that time of year to achieve the desired results. However, if it is maximising grain yield then sowing within the recommended window is ideal. For more information feel free to contact your local LLS Ag Advisor.

Further Resources:

Brooking I (1996) Temperature Response of Vernalization in Wheat: A Developmental Analysis, Annals of Botany, 78 (4), pp. 507-512

Commonwealth of Australia (2020) CliMate. Available at: https://climateapp.net.au/

GRDC (2016) GRDC Grow Notes - February 2016. Available at: https://grdc.com.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0025/370672/GrowNote-Wheat-North-03-Planting.pdf

Harris F, Martin P, Eagles H (2016) Understanding wheat phenology: flowering response to sowing time, GRDC Update Papers. Available at: https://grdc.com.au/resources-and-publications/grdc-update-papers/tab-content/grdc-update-papers/2016/02/understanding-wheat-phenology-flowering-response-to-sowing-time

Haskins B (2011) Cropping to fill the feed gap. NSW DPI Ag Today Archives. Available at: https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/content/archive/agriculture-today-stories/ag-today-archives/agriculture_today_march_2006/2006-003/cropping_to_fill_the_feed_gap

Hennessy G, Clements B (2009) Cereals for grazing. NSW DPI Primefacts. Available at: https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/288191/Cereals-for-grazing.pdf

Matthews P, McCaffery D, Jenkins L (2020) NSW DPI - Winter Crop Variety Sowing Guide. Available at: https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/1211729/FINAL-WCVSG-2020-web.pdf

Thompson C (2020) Sowing Oats Early - Yes Or No? Central West Local Land Services. Available at: https://www.lls.nsw.gov.au/regions/central-west/articles-and-publications/crop-production/sowing-oats-early-yes-or-no