Look out for lepto

06 Oct 2021

PRODUCTION ADVICE - OCTOBER 2021 - ANIMAL BIOSECURITY & WELFARE

By Meg Martin

Veterinary Student

While heavy rainfall throughout winter and coming into spring does wonders for pasture growth, it comes paired with an increased risk of diseases that thrive in warm, moist environments. Leptospirosis is one of these diseases, and it has the potential to have major impacts both on the health of your herds and your profit margin.

While heavy rainfall throughout winter and coming into spring does wonders for pasture growth, it comes paired with an increased risk of diseases that thrive in warm, moist environments. Leptospirosis is one of these diseases, and it has the potential to have major impacts both on the health of your herds and your profit margin.

What is it?

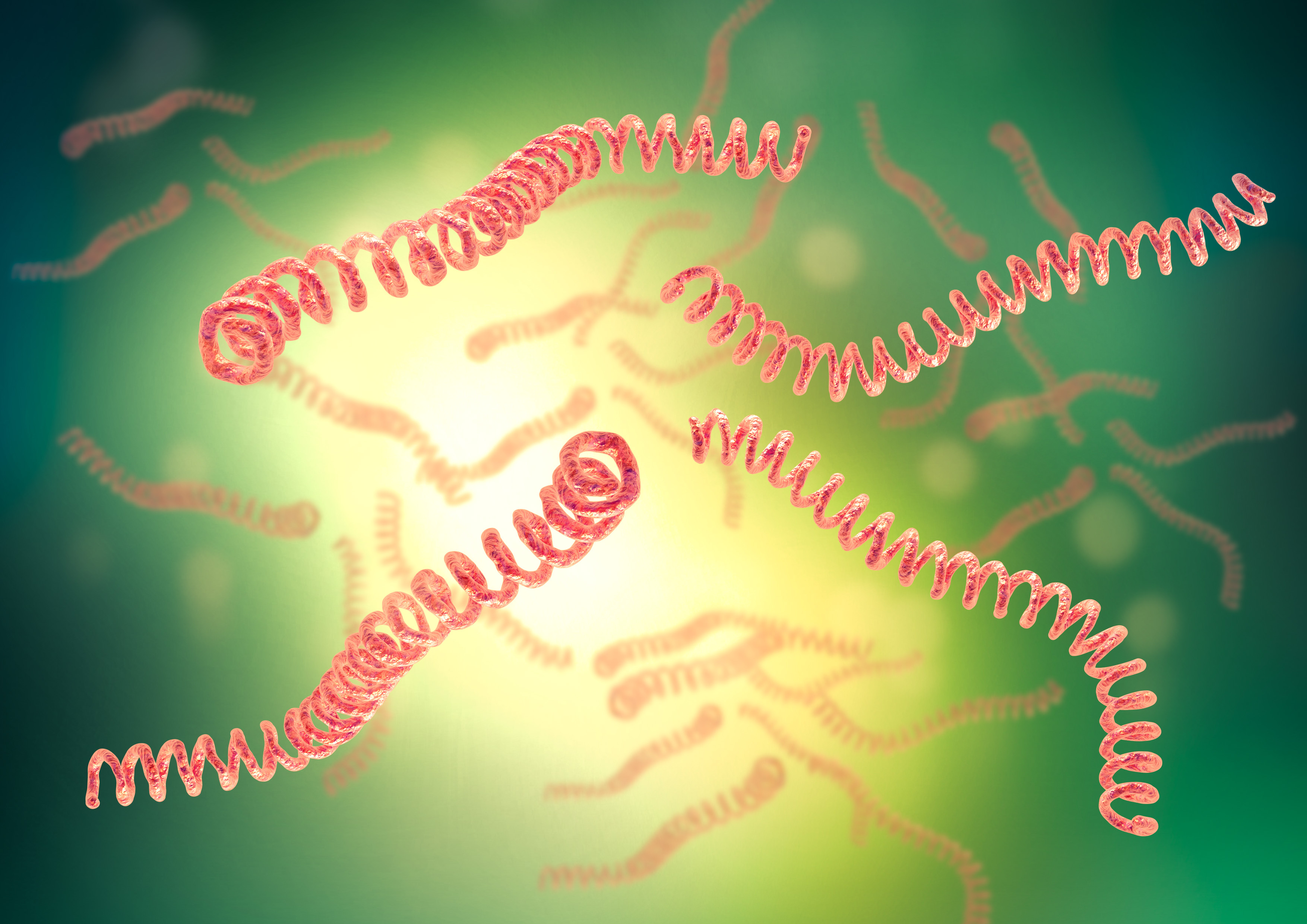

Leptospirosis is a disease of animals and humans caused by infection with Leptosira bacteria. While there are hundreds of different strains, the two most important to Australian livestock producers are Leptospira hardjo-bovis (cattle) and Leptospira pomona (pigs, cattle). Both are zoonotic and may cause severe illness in humans.

More information about clinical signs in humans can be found from your doctor or NSW health Leptospirosis fact sheet - Fact sheets (nsw.gov.au)

How is it spread?

Infected animals can shed the bacteria in their urine or during birth and abortions, contaminating the pasture, soil and water sources. The bacteria can survive for several weeks in the environment and thrive in warmth and moisture, favouring damp or muddy soil, but are quickly killed on dry soil or by sunlight.

Flooding after heavy rain can spread the bacteria to previously uninfected farms. Outbreaks are therefore more common in wet years. The bacteria may then infect naïve animals and humans through damaged skin or the membranes of the nose, eyes or mouth.

What are the clinical signs of lepto?

Clinical signs in livestock may include:

- transient mastitis (usually self-resolving in 10-14 days), characterised by a sudden drop in milk production, possible fever, mastitic milk changes and flaccid udder tone

- reddish-brown urine in calves as young as two weeks old

- anorexia

- rapid breathing

- jaundiced mucous membranes (pale yellow discolouration in mouth and vagina)

- rough and dry coat

- anaemia

- lethargy and depression

- high fever in young animals

- death in severe cases (generally only seen in young animals).

Chronic infections often result in the bacteria being harboured in the kidneys, causing persistent shedding in the urine.

Subclinical disease mainly affects an animal’s reproductive performance, causing:

- embryonic death

- abortions

- stillbirths

- retained placentae

- birth of weak or non-viable offspring

- infertility caused by persistent infection in the reproductive tract.

There is likely to be a higher rate of abortion in a herd when they are first exposed. The stage of gestation will also influence the outcome of the pregnancy: infection in early gestation may result in embryonic death or abortions; infection during late gestation may cause stillborn or weak offspring. Sometimes the offspring born after being infected during pregnancy become chronic carriers of infection.

Diagnosis

Blood samples from a representative sample of an unvaccinated herd can be used to test for Leptospira antibodies. Diagnosis can also come from testing an aborted foetus (membranes included) or kidney retrieved from necropsy.

Management and prevention

While treatment is possible with antibiotics, prevention of leptospirosis is the much better option from a practical, financial and welfare point of view.

As with any infectious disease control strategies, adequate biosecurity measures are vital in preventing the introduction of disease onto a property and minimising the spread when disease is already present.

Standard biosecurity measures include:

- quarantining any new animals upon arrival to the property

- maintaining secure fencing to prevent unwanted mixing of animals on the property and minimise the risk of pests bringing in disease

- pest control measures, particularly targeting feral pigs

- restricting access to potentially contaminated water sources

- keeping livestock on clean, good-quality paddocks and avoiding land that is boggy and may be contaminated by run-off

- avoiding allowing different species of livestock to contact one another (e.g. mixing cattle and sheep herds; grazing sheep near pet pigs)

- Implementing a vaccination program

- Wearing basic personal protective equipment (PPE) such as gloves and a mask when there is the risk of encountering animal urine and washing hands thoroughly after handling stock

Vaccination

Prevention via vaccination is the most effective way of preventing leptospirosis in cattle or pigs. With veterinary consultation, a vaccination program can be established on-farm to boost herd immunity to infection, prevent urine shedding of bacteria and minimise the risk of associated reproductive issues. Protection is established via two initial doses of the vaccine four weeks apart followed by an annual booster.

Prevention is better than cure. Ensure that you protect your livestock, and farm workers, from lepto infections.

For more information or advice, contact our District Vets on 03 5881 9900 (Deniliquin) or 02 6051 2200 (Albury).